A Tree, in Many Ways, an External Lung

- Team In-De

- Jan 4

- 4 min read

Fractal Lungs, Fractal Trees, and the Blueprint of Design

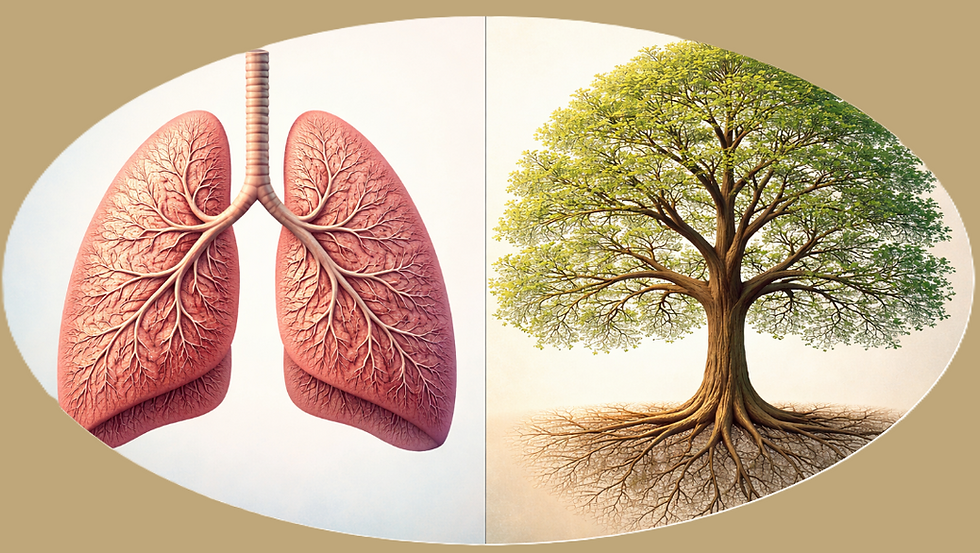

There are moments when two things, placed side by side, quietly change the way we see the world.

A human lung and a tree seem unrelated at first glance. One is hidden within the body, soft and unseen. The other stands openly in soil and sunlight, strong and enduring. One sustains individual life; the other supports ecosystems. Yet when we look past appearances and into structure, a deeper truth reveals itself.

They share the same design.

Not symbolically. Not poetically. Structurally.

Both lungs and trees are built upon fractal branching—a repeating pattern where the same form appears again and again at smaller scales. This pattern is not decorative. It is purposeful. It is the most efficient solution to a shared problem: how to move something essential to countless endpoints within limited space.

The resemblance invites a simple but profound question: Why does the same pattern appear wherever life must breathe?

Fractals: The Language of Order

A fractal is a pattern that repeats across scale. Zoom in, and the structure resembles the whole. Zoom out, and the same logic remains. Fractals appear throughout creation: river systems, lightning, snowflakes, blood vessels, neurons, lungs, and trees.

Fractals are not chaotic. They are ordered.

They maximize surface area while minimizing material. They distribute resources efficiently. They allow growth without redesign. Wherever complexity must function smoothly, fractal design appears.

Nature relies on repetition with purpose. Beauty follows function—not the other way around.

The Lung: Breath Through Branching

The human lung is a marvel of intentional structure.

Air enters through the trachea and divides into two bronchi. These branch again into bronchioles, forming an intricate network that fills the chest. At the smallest scale, the branches end in millions of tiny air sacs called alveoli.

These alveoli create an enormous surface area. If laid flat, the alveoli of one adult lung would cover an area roughly the size of a tennis court.

That surface area exists for one reason: efficient gas exchange.

Oxygen must enter the bloodstream quickly. Carbon dioxide must exit just as reliably. The fractal structure ensures that every red blood cell passes close enough to oxygen to sustain life.

Straight tubes would fail. A single chamber would fail. Only branching—precise, repeated, ordered branching—solves the problem within the space of the human body.

The lung is not shaped this way by chance. It is shaped this way because the design works.

A Tree, in Many Ways, an External Lung

A tree performs the same essential task—only outwardly.

Its branches divide again and again, spreading leaves across space to capture sunlight. Its roots mirror this pattern beneath the soil, absorbing water and nutrients. Leaves exchange gases with the atmosphere, taking in carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen.

Where lungs breathe for an individual, trees breathe for the planet.

The tree’s structure is not ornamental. It is functional. It maximizes exposure while minimizing material. It allows growth from sapling to towering canopy without altering the underlying pattern.

A tree does not need to reinvent itself as it grows. It simply extends what is already there.

In this sense, a tree truly is an external lung—built upon the same logic, serving life on a broader scale.

The Same Pattern, Turned Inside and Out

The similarity between lungs and trees is not superficial. It is mathematical.

Both systems follow predictable branching rules. The diameter of branches decreases in orderly steps. The angles of division reduce resistance. Flow is preserved from trunk to tip, from trachea to alveoli.

This is why engineers study these structures. Ventilation systems, plumbing networks, and data structures all borrow from branching logic. Human design succeeds most often when it mirrors designs already present in creation.

We do not invent these patterns. We recognize them.

Efficiency Reflects Intentional Order

Efficiency is not random.

Fractal systems appear wherever something essential must reach many places quickly and reliably. They reduce waste. They increase resilience. They allow systems to continue functioning even when parts are damaged.

A lung can lose capacity and still breathe. A tree can lose branches and still live.

Strength is distributed rather than centralized. The design anticipates stress rather than reacting to it.

Such foresight embedded in structure points to order—not accident.

A Shared Blueprint Across Creation

When lungs and trees are viewed together, they reveal a unifying truth: creation operates according to a consistent design language.

Fractals are part of that language, alongside spirals, symmetry, and cycles. These patterns appear across living systems and physical structures alike, suggesting coherence rather than chaos.

Different purposes. Same principles.

The blueprint does not change with scale or setting. It is applied consistently, whether inside the human body or across the landscape.

Borrowing the Blueprint

Modern science openly acknowledges this through biomimicry—design inspired by nature. Engineers study lungs to improve airflow. Designers study trees to optimize networks. Medicine, architecture, and technology advance by observing what already works.

Human creativity flourishes when it studies and applies designs already present.

Yet often, the deeper implication is left unspoken.

We borrow the blueprint. We celebrate the solution. But we hesitate to acknowledge the source.

The Body as Part of Creation

The lung–tree comparison reminds us that the human body is not separate from nature. It is continuous with it.

Our internal structures mirror external systems. Our survival depends on the same principles that govern forests, rivers, and skies. We are sustained by patterns found both within us and around us.

This continuity invites humility—and wonder.

Conclusion: A Quiet Testimony of Design

The comparison between fractal lungs and fractal trees does not argue loudly. It simply shows.

A tree, in many ways, is an external lung. A lung, in many ways, is an internal tree.

Different environments. Same blueprint.

Such consistency invites reflection. Order appears before explanation. Structure precedes function. Pattern reveals purpose.

The blueprint was present before we arrived. And every breath we take quietly points back to it.

Comments